Introduction

Aanii boozhoo nwiijkiwenhak! Welcome to a new year, and welcome back. Today we’re going to be talking about a book that I stumbled on in our collection. From Publishers Weekly:

As an author’s note explains, Ahnighito is the name of the enormous meteorite now housed in New York City’s Museum of Natural History, transported there from the North Pole in 1897. Conrad (The Tub People) imagines the thoughts and feelings of Ahnighito from “her” arrival on earth to her installation in the museum. As cold years go by at the North Pole, various people take an interest, chipping away at the rock; finally, over a series of winters, members of the Peary expedition haul her to the ocean and heave her onto a ship. Life becomes more interesting as Ahnighito travels to Brooklyn, then across Manhattan to the museum.

Publishers Weekly site

It’s already kind of a lot just based on the cover, so let’s dive right in.

The Not-So-Good Stuff

Let’s work from the outside in.

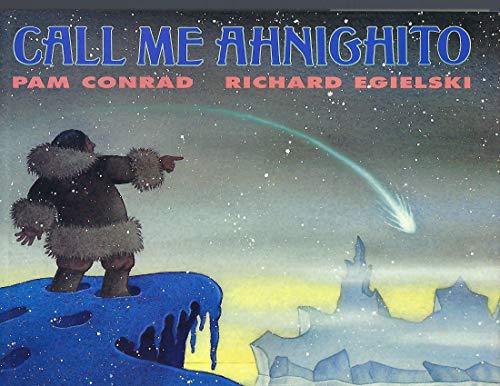

The cover presents us with an arresting image. I wasn’t familiar with Ahnighito at all prior to reading this book, so I had zero context for why an Inuk(?) person might be pointing at a shooting star. The image wraps around the entire cover, showing us what appears to be three Inuit folks and a howling wolf standing on top of an icy outcropping. At first blush, I thought that maybe this would be a story about an Inuk explorer or something similar, but it turns out that Ahnighito is a meteorite. This link will take you to the American Museum of Natural History’s website about it, as it’s still housed there today.

The story is told from the meteorite’s point of view. Although it’s in picture book format, the text is definitely more intended to be adult-guided or for an older reader. The meteorite as a character takes us through its long history from its impact on Earth to how it came to be housed in the American Museum of Natural History. The images seem to take shape around the text; the 1-2 paragraphs per page are presented in a white rectangle with a black border on every page that they appear. The images themselves go from extremely simple – the meteorite half-buried in the snow – to busy and complex as the story goes from the Arctic to Manhattan. The final image we see is of the meteorite in its current position as a highlighted artifact in the museum. We are left with these final words:

Now I am at my most glorious. … I am no longer lonely. Everyone knows my name. They call me Ahnighito.

unpaginated final page

“Allie,” you may be asking your computer screen, “why are you mad at a book about a rock?”

I’m hoping you’re willing to hear me out about it!

I mentioned the cover at the beginning of this section – part of the reason it drew me in was because of the imagery of Inuit people potentially exploring or discovering something. While this does happen in the story, it is presented extremely briefly and is quickly glossed over in favor of the white explorers who make contact and then take the meteorite to America. If Inuit voices aren’t prioritized and they’re not main characters, why are they featured so prominently on the cover? It’s clear that the creators of this book knew that this imagery is eye-catching – Indigenous people are featured on the cover despite not being a major part of the story because the book’s creators knew it would draw people to the story.

The imagery continues to be problematic throughout the story as well. I mentioned earlier that the illustrations get more complex as the story goes on – this could be attributed to the meteorite’s experience expanding as it travels from Greenland to New York. That said, however, the increase in detail also coincides heavily with the appearance of white explorers and their technologies. White characters also have variations in their clothing, different gender presentations, and decorations that aren’t present for the Inuit characters (even in their brief appearances). Facial expressions also don’t change much for the Inuit characters despite the white characters being given a range of emotions to feel. The white people shown in the story have a lot more agency than the Inuit characters overall. The meteorite also seems to side heavily with the white characters. It celebrates its discovery by the Inuit at first, but then worries about being “chipped away to nothing” by the Inuit who use its metal to make things. The important thing to know here is that I’ve been assuming Inuit this entire time – the people who first discover the meteorite in the ice are never named! The meteorite as a character calls them “the snow people” but somehow knows the names Greenland, Brooklyn, and Manhattan?

Overall, this presentation of Ahnighito’s story is lazy. Conrad is clearly uninterested in telling the actual story of Ahnighito’s discovery and removal from Greenland to Manhattan. This article from the New York Times talks more about Peary’s expedition that happened upon the meteorite, including his kidnapping of Indigenous people after using their expertise to navigate the Arctic. This story presents a harmfully romanticized view of colonial exploits in the Arctic in a way that doesn’t create an opportunity for questions about the Indigenous people involved in the story but benefits heavily from their imagery and presence.

In Summary

I’m hoping this book isn’t too much of a bummer, but I thought it was important to talk about! Because of its poor representation and promulgation of colonial fairy tales, this book is not recommended. That said, I encourage you to check this book out and use it as an example of Indigenous imagery excluding Indigenous agency!

Call Me Ahnighito is written by Pam Conrad and illustrated by Richard Egielski. It’s published by Laura Geringer, an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers. Publishers Weekly has links to purchase it here. As always, gichi miigwech for reading!